Louis Lambert (novel) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Louis Lambert'' is an 1832 novel by French novelist and playwright

By 1832,

By 1832,

In May 1832, Balzac suffered a head injury when his

In May 1832, Balzac suffered a head injury when his

The religious theme later appears in passages relating to

The religious theme later appears in passages relating to

Balzac was fiercely proud of ''Louis Lambert'' and believed that it elegantly represented his diverse interests in philosophy, mysticism, religion, and occultism. When he sent an early draft to his lover at the time, however, she predicted the negative reception it would receive. "Let the whole world see you for themselves, my dearest," she wrote, "but do not cry out to them to admire you, because then the most powerful magnifying glasses will be directed at you, and what becomes of the most exquisite object when it is put under a microscope?" Critical reaction was overwhelmingly negative, due mostly to the book's lack of sustaining narrative. Conservative commentator Eugène Poitou, on the other hand, accused Balzac of lacking true faith and portraying the French family as a vile institution.

Balzac was undeterred by the negative reactions; referring to ''Louis Lambert'' and the other works in ''Le Livre mystique'', he wrote: "Those are books that I create for myself and for a few others." Although he was often critical of Balzac's work, French author

Balzac was fiercely proud of ''Louis Lambert'' and believed that it elegantly represented his diverse interests in philosophy, mysticism, religion, and occultism. When he sent an early draft to his lover at the time, however, she predicted the negative reception it would receive. "Let the whole world see you for themselves, my dearest," she wrote, "but do not cry out to them to admire you, because then the most powerful magnifying glasses will be directed at you, and what becomes of the most exquisite object when it is put under a microscope?" Critical reaction was overwhelmingly negative, due mostly to the book's lack of sustaining narrative. Conservative commentator Eugène Poitou, on the other hand, accused Balzac of lacking true faith and portraying the French family as a vile institution.

Balzac was undeterred by the negative reactions; referring to ''Louis Lambert'' and the other works in ''Le Livre mystique'', he wrote: "Those are books that I create for myself and for a few others." Although he was often critical of Balzac's work, French author

Balzac as Anthropologist

(on Louis Lambert). ''Anthropoetics'' VI, 1, 2000, 1–15. * Sprenger, Scott. ""Balzac, Archéologue de la conscience," Archéomanie: La mémoire en ruines, eds.Valérie-Angélique Deshoulières et Pascal Vacher, Clermont Ferrand: Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal, CRLMC, 2000, 97–114. * Stowe, William W. ''Balzac, James, and the Realistic Novel''. Princeton:

''Louis Lambert''

at

Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly , ; born Honoré Balzac;Jean-Louis Dega, La vie prodigieuse de Bernard-François Balssa, père d'Honoré de Balzac : Aux sources historiques de La Comédie humaine, Rodez, Subervie, 1998, 665 p. 20 May 179 ...

(1799–1850), included in the ''Études philosophiques'' section of his novel sequence

A book series is a sequence of books having certain characteristics in common that are formally identified together as a group. Book series can be organized in different ways, such as written by the same author, or marketed as a group by their pub ...

''La Comédie humaine

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figure ...

''. Set mostly in a school at Vendôme

Vendôme (, ) is a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Departments of France, department of Loir-et-Cher, France. It is also the department's third-biggest Communes of France, commune with 15,856 inhabitants (2019).

It is one of the ...

, it examines the life and theories of a boy genius fascinated by the Swedish philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had ...

(1688–1772).

Balzac wrote ''Louis Lambert'' during the summer of 1832 while he was staying with friends at the Château de Saché

The Château de Saché is a writer's house museum located in a home built from the converted remains of a feudal castle. Located in Saché, Indre-et-Loire, between 1830 and 1837, it is where French writer Honoré de Balzac wrote many of his nov ...

, and published three editions with three different titles. The novel contains a minimal plot, focusing mostly on the metaphysical ideas of its boy-genius protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

and his only friend (eventually revealed to be Balzac himself). Although it is not a significant example of the realist style for which Balzac became famous, the novel provides insight into the author's own childhood. Specific details and events from the author's life – including punishment from teachers and social ostracism

Ostracism ( el, ὀστρακισμός, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the cit ...

– suggest a fictionalized autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

.

While he was a student at Vendôme, Balzac wrote an essay called ''Traité de la Volonté'' ("Treatise on the Will"); it is described in the novel as being written by Louis Lambert. The essay discusses the philosophy of Swedenborg and others, although Balzac did not explore many of the metaphysical concepts until much later in his life. Ideas analyzed in the essay and elsewhere in the novel include the split between inward and outward existence; the presence of angels

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles incl ...

and spiritual enlightenment; and the interplay between genius and madness.

Although critics panned the novel, Balzac remained steadfast in his belief that it provided an important look at philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

, especially metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

. As he developed the scheme for ''La Comédie humaine'', he placed ''Louis Lambert'' in the ''Études philosophiques'' section, and later returned to the same themes in his novel ''Séraphîta

''Séraphîta'' () is a French novel by Honoré de Balzac with themes of androgyny. It was published in the ''Revue de Paris'' in 1834. In contrast with the realism of most of the author's best known works, the story delves into the fantastic an ...

'', about an androgynous

Androgyny is the possession of both masculine and feminine characteristics. Androgyny may be expressed with regard to biological sex, gender identity, or gender expression.

When ''androgyny'' refers to mixed biological sex characteristics i ...

angelic creature.

Background

By 1832,

By 1832, Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly , ; born Honoré Balzac;Jean-Louis Dega, La vie prodigieuse de Bernard-François Balssa, père d'Honoré de Balzac : Aux sources historiques de La Comédie humaine, Rodez, Subervie, 1998, 665 p. 20 May 179 ...

had begun to make a name for himself as a writer. The second of five children, Balzac was sent to the Oratorian College de Vendôme

Vendôme (, ) is a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Departments of France, department of Loir-et-Cher, France. It is also the department's third-biggest Communes of France, commune with 15,856 inhabitants (2019).

It is one of the ...

at the age of eight. He returned from the school six years later, sickly and weak. He was taught by tutors and private schools for two and a half years, then attended the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. After training as a law clerk

A law clerk or a judicial clerk is a person, generally someone who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial clerks often play significant ...

for three years, he moved into a tiny garret

A garret is a habitable attic, a living space at the top of a house or larger residential building, traditionally, small, dismal, and cramped, with sloping ceilings. In the days before elevators this was the least prestigious position in a bu ...

in 1819 and began writing.

His first efforts, published under a variety of pseudonyms, were cheaply printed potboiler

A potboiler or pot-boiler is a novel, play, opera, film, or other creative work of dubious literary or artistic merit, whose main purpose was to pay for the creator's daily expenses—thus the imagery of "boil the pot", which means "to provide one ...

novels. In 1829 he finally released a novel under his own name, titled ''Les Chouans

''Les Chouans'' (, ''The Chouans'') is an 1829 novel by French novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) and included in the ''Scènes de la vie militaire'' section of his novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine''. Set in the French ...

''; it was a minor success, though it did not earn the author enough money to relieve his considerable debt. He found fame soon afterwards with a series of novels including ''La Physiologie du mariage'' (1829), ''Sarrasine

''Sarrasine'' is a novella written by Honoré de Balzac. It was published in 1830, and is part of his '' Comédie Humaine''.

Introduction

Balzac, who began writing in 1819 while living alone in the rue Lesdiguières, undertook the composition ...

'' (1830), and ''La Peau de chagrin

''La Peau de chagrin'' (, ''The Skin of Shagreen''), known in English as ''The Magic Skin and The Wild Ass's Skin'', is an 1831 novel by French novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850). Set in early 19th-century Paris, it tells t ...

'' (1831).

In 1831 Balzac published a short story called "Les Proscrits

''Les Proscrits'' (sometimes translated into English as ''The Exiles'') is a French short story by Honoré de Balzac, published in 1831 by éditions Gosselin, then in 1846 by Furne, Dubochet, Hetzel in ''Études philosophiques''. He subtitled it ...

" ("The Exiles"), about two poets named Dante and Godefroid de Gand who attend the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

at the start of the fourteenth century. It explores questions of metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

and mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

, particularly the spiritual quest for illuminism

The Illuminati (; plural of Latin ''illuminatus'', 'enlightened') is a name given to several groups, both real and fictitious. Historically, the name usually refers to the Bavarian Illuminati, an Enlightenment-era secret society founded on ...

and enlightenment. Balzac had been influenced greatly as a young man by the Swedish philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had ...

, whose theories permeate "Les Proscrits". The story was published – alongside ''La Peau de chagrin'', which also delves into metaphysics – as part of an 1831 collection entitled ''Romans et contes philosophiques'' ("Philosophical novels and stories").

Writing and publication

In May 1832, Balzac suffered a head injury when his

In May 1832, Balzac suffered a head injury when his tilbury

Tilbury is a port town in the borough of Thurrock, Essex, England. The present town was established as separate settlement in the late 19th century, on land that was mainly part of Chadwell St Mary. It contains a 16th century fort and an ancie ...

carriage crashed in a Parisian street. Although he was not hurt badly, he wrote to a friend about his worry that "some of the cogs in the mechanism of my brain may have got out of adjustment". His doctor ordered him to rest and refrain from writing and other mental activity. When he had recuperated, he spent the summer at the Château de Saché

The Château de Saché is a writer's house museum located in a home built from the converted remains of a feudal castle. Located in Saché, Indre-et-Loire, between 1830 and 1837, it is where French writer Honoré de Balzac wrote many of his nov ...

, just outside the city of Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 ...

, with a family friend, Jean de Margonne.

While in Saché, he wrote a short novel called ''Notice biographique sur Louis Lambert'' about a misfit boy genius interested in metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

. Like "Les Proscrits", ''Louis Lambert'' was a vehicle for Balzac to explore the ideas that had fascinated him, particularly those of Swedenborg and Louis Claude de Saint-Martin

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin (18 January 1743 – 14 October 1803) was a French philosopher, known as ''le philosophe inconnu'', the name under which his works were published; he was an influential of the mystic and human mind evolution and ...

. He hoped the work would "produce an effect of incontestable superiority". and provide "a glorious rebuttal" to critics who ridiculed his interest in metaphysics.

The novel was first published as part of the ''Nouveaux contes philosophiques'' in late 1832, but by the start of the following year he declared it to be "a wretched miscarriage" and began rewriting it. During the process, Balzac was aided by a grammarian working as a proofreader, who found "a thousand errors" in the text. Once he had returned home, the author "cried with despair and with that rage that takes hold of you when you recognize your faults after working so hard".

A vastly expanded and revised novel, ''Histoire intellectuelle de L.L.'', was published as a single volume in 1833. Balzac, still unsatisfied, continued reworking the text – as he often did between editions – and included a series of letters written by the boy genius, as well as a detailed description of his metaphysical theories. This final edition was released as ''Louis Lambert'', included with "Les Proscrits" and a later work, ''Séraphîta'', in a volume entitled ''Le Livre mystique'' ("The Mystical Book").

Plot summary

The novel begins with an overview of the main character's background. Louis Lambert, the only child of a tanner and his wife, is born in 1797 and begins reading at an early age. In 1811 he meets the real-life Swiss authorMadame de Staël Madame may refer to:

* Madam, civility title or form of address for women, derived from the French

* Madam (prostitution), a term for a woman who is engaged in the business of procuring prostitutes, usually the manager of a brothel

* ''Madame'' ...

(1766–1817), who – struck by his intellect – pays for him to enroll in the Collège de Vendôme. There he meets the narrator, a classmate named "the Poet" who later identifies himself in the text as Balzac; they quickly become friends. Shunned by the other students and berated by teachers for not paying attention, the boys bond through discussions of philosophy and mysticism.

After completing an essay entitled ''Traité de la Volonté'' ("Treatise on the Will"), Lambert is horrified when a teacher confiscates it, calls it "rubbish", and – the narrator speculates – sells it to a local grocer. Soon afterwards, a serious illness forces the narrator to leave the school. In 1815, Lambert graduates at the age of eighteen and lives for three years in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. After returning to his uncle's home in Blois

Blois ( ; ) is a commune and the capital city of Loir-et-Cher department, in Centre-Val de Loire, France, on the banks of the lower Loire river between Orléans and Tours.

With 45,898 inhabitants by 2019, Blois is the most populated city of the ...

, he meets a woman named Pauline de Villenoix and falls passionately in love with her. On the day before their wedding, however, he suffers a mental breakdown and attempts to castrate himself.

Declared "incurable" by doctors, Lambert is ordered into solitude and rest. Pauline takes him to her family's château, where he lives in a near coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

. The narrator, ignorant of these events, meets Lambert's uncle by chance, and is given a series of letters. Written by Lambert while in Paris and Blois, they continue his philosophical musings and describe his love for Pauline. The narrator visits his old friend at the Villenoix château, where the decrepit Lambert says only: "The angels are white." Pauline shares a series of statements her lover had dictated, and Lambert dies on 25 September 1824 at the age of twenty-eight.

Style

The actual events of ''Louis Lambert'' are secondary to extended discussions of philosophy (especially metaphysics) and human emotion. Because the novel does not employ the same sort ofrealism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

for which Balzac became famous, it has been called one of "the most diffuse and least valuable of his works". Whereas many Balzac stories focus on the external world, ''Louis Lambert'' examines many aspects of the thought process and the life of the mind. Many critics, however, condemn the author's disorganized style and his placement of his own mature philosophies into the mind of a teenage boy.

Still, shades of Balzac's realism are found in the book, particularly in the first-hand descriptions of the Collège de Vendôme. The first part of the novel is replete with details about the school, describing how quarters were inspected and the complex social rules for exchanging dishes at dinnertime. Punishments are also described at length, including the assignment of tedious writing tasks and the painful application of the strap

A strap, sometimes also called strop, is an elongated wikt:flap, flap or ribbon, usually of leather or other flexible materials.

Thin straps are used as part of clothing or baggage, or bedding such as a sleeping bag. See for example spaghetti s ...

: Of all the physical torments to which we were exposed, certainly the most acute was that inflicted by this leathern instrument, about two fingers wide, applied to our poor little hands with all the strength and all the fury of the administrator. To endure this classical form of correction, the victim knelt in the middle of the room. He had to leave his form and go to kneel down near the master's desk under the curious and generally merciless eyes of his fellows.... Some boys cried out and shed bitter tears before or after the application of the strap; others accepted the infliction with stoic calm ... but few could control an expression of anguish in anticipation.Further signs of Balzac's realism appear when Lambert describes his ability to vicariously experience events through thought alone. In one extended passage, he describes reading about the

Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz in ...

and seeing "every incident". In another he imagines the physical pain of a knife cutting his skin. As Balzac's biographer André Maurois notes, these reflections provide insight into the author's perspective toward the world and its written representations.

Themes

Autobiography

Biographers and critics agree that Louis Lambert is a thinly veiled version of the author, evidenced by numerous similarities between them. As a student at the Collège de Vendôme, Balzac was friends with a boy named Louis-Lambert Tinant. Like the title character, Balzac's faith was shaken at the time of his first communion. Balzac read voraciously while in school, and – like Lambert – was often punished for misbehaving in class. The precise details of the school also reflect Balzac's time there: as described in the novel, students were allowed to keeppigeons

Columbidae () is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with short necks and short slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. They primarily ...

and tend gardens, and holidays were spent in the dormitories

A dormitory (originated from the Latin word ''dormitorium'', often abbreviated to dorm) is a building primarily providing sleeping and residential quarters for large numbers of people such as boarding school, high school, college or university s ...

.

Lambert's essay about metaphysics, ''Traité de la Volonté'' ("Treatise on the Will"), is another autobiographical reference. Balzac wrote the essay himself as a boy, and – as in the novel – it was confiscated by an angry teacher. Lambert's genius and philosophical erudition are reflections of Balzac's self-conception. Similarly, some critics and biographers have suggested that Lambert's madness reflects (consciously or not) Balzac's own unsteady mental state. His plans to run for parliament and other non-literary ambitions led observers at the time to suspect his sanity.

The many letters in the novel written by Lambert are also based on Balzac's life. After finishing the first version of the book, Balzac tried to win the heart of the Marquise de Castries by sending her a fragmented love letter from the book. Lambert's letters to his uncle about life in Paris from 1817 to 1820, meanwhile, mirror Balzac's own sentiments while attending the Sorbonne at the same time.

Swedenborg and metaphysics

The ideas ofSwedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had ...

(and his disciple Louis Claude de Saint-Martin

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin (18 January 1743 – 14 October 1803) was a French philosopher, known as ''le philosophe inconnu'', the name under which his works were published; he was an influential of the mystic and human mind evolution and ...

) are central to ''Louis Lambert''. Madame de Staël is impressed by Lambert when she finds him in a park reading Swedenborg's metaphysical treatise '' Heaven and Hell'' (1758); the Swedish writer's ideas are later reproduced in Lambert's own comments about mind, soul, and will. Primary among these is the division of the human into an "inward" and "outward" being. The outward being, subject to the forces of nature and studied by science, manifests itself in Lambert as the frail, frequently sick boy. The inward being, meanwhile, contains what Lambert calls "the material substance of thought", and serves as the true life into which he gradually moves throughout the novel.

Swedenborg's concepts are explored with relation to language, pain, memory, and dreams. When the students take a trip to the nearby Château de Rochambeau, for example, Lambert, who has never visited the château, nevertheless recalls vivid memories of the place from a dream. Believing his spirit visited the place while his body slept, he ascribes the experience to "a complete severance of my body and my inner being" and "some inscrutable locomotive faculty in the spirit with effects resembling those of locomotion in the body".

Like his heroes Swedenborg and Saint-Martin, Balzac attempts in ''Louis Lambert'' to construct a viable theory to unify spirit and matter. Young Lambert attempts this goal in his ''Traité de la Volonté'', which – having been confiscated by a teacher – is described by the narrator:The word Will he used to connote ... the mass of power by which man can reproduce, outside himself, the actions constituting his external life.... The word Mind, or Thought, which he regarded as the quintessential product of the Will, also represented the medium in which the ideas originate to which thought gives substance.... Thus the Will and the Mind were the two generating forces; the Volition and the Idea were the two products. Volition, he thought, was the Idea evolved from the abstract state to a concrete state, from its generative fluid to a solid expression.... According to him, the Mind and Ideas are the motion and the outcome of our inner organization, just as the Will and Volition are of our external activity. He gave the Will precedence over the Mind.The exploration of human will and thought is linked to Balzac's interest in

Franz Mesmer

Franz Anton Mesmer (; ; 23 May 1734 – 5 March 1815) was a German physician with an interest in astronomy. He theorised the existence of a natural energy transference occurring between all animated and inanimate objects; this he called " ani ...

, who postulated the theory of animal magnetism

Animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, was a protoscientific theory developed by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century in relation to what he claimed to be an invisible natural force (''Lebensmagnetismus'') possessed by all livi ...

, a force flowing among humans. The narrator invokes Mesmer twice in the text, and describes a section of the ''Traité de la Volonté'' which reflects the animal-magnetic theory.

Religion

Balzac's spiritual crisis at the time of his first communion led him to explore the first Christian thinkers and the question of evil. As the French critic Philippe Bertault points out, much of the mysticism in ''Louis Lambert'' is related to that of earlyChristianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

. In his letters, Lambert describes exploring the philosophies of Christianity, Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

, Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

, Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, and Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

, among others. Tracing the similarities among these traditions, he declares that Swedenborg "undoubtedly epitomizes all of the religions—or rather the one religion—of humanity". The same theory informs Balzac's efforts, in ''Louis Lambert'' and elsewhere, to complement his Christian beliefs with occult mysticism and secular realism.

The church itself is a subject of Lambert's meditations, particularly with regard to the early Christian martyrs

In Christianity, a martyr is a person considered to have died because of their testimony for Jesus or faith in Jesus. In years of the early church, stories depict this often occurring through death by sawing, stoning, crucifixion, burning at th ...

. The split between inward and outward realities, he suggests, serves to explain the ability of those being tortured and maimed to escape physical suffering through the will of the spirit. As Lambert says: "Do not the phenomena observed in almost every instance of the torments so heroically endured by the early Christians for the establishment of the faith, amply prove that Material force will never prevail against the force of Ideas or the Will of man?" This inward–outward split also serves to explain the Miracles attributed to Jesus

The miracles of Jesus are miraculous deeds attributed to Jesus in Christian and Islamic texts. The majority are faith healings, exorcisms, resurrections, and control over nature.

In the Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke), Jesus r ...

, whom Lambert considers a "perfect" representation of unity between the two beings.

The religious theme later appears in passages relating to

The religious theme later appears in passages relating to angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles include ...

s. Discussing the contents of Swedenborg's ''Heaven and Hell'', Lambert tries to convince the narrator of the existence of angels, described as "an individual in whom the inner being conquers the outer being". The boy genius himself is seen as an example of this process: his physical body withers and sickens, while his spiritual enlightenment expands, reaching its apex with his comment to the narrator: "The angels are white." Pauline, meanwhile, is described as "the angel" and "Angel-woman". Their parallel angelic states merge into what critic Charles Affron calls "a kind of perfect marriage, a spiritual bond that traverses this world and the next". Balzac later returned to the question of angels in other works of the ''Études philosophiques'', particularly ''Séraphîta''.

Genius and madness

Convinced that he was himself agenius

Genius is a characteristic of original and exceptional insight in the performance of some art or endeavor that surpasses expectations, sets new standards for future works, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabiliti ...

, Balzac used ''Louis Lambert'' to explore the difficulty of geniuses in society, as well as their frequent progression into madness. He had been troubled greatly when, at Vendôme, he watched a schoolmate's mental condition deteriorate severely. Lambert's madness is represented most vividly in his attempt at self-castration

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharmaceut ...

, followed by years spent in a catatonic state. This transformation is in many ways a byproduct of his genius; because his brilliance is condemned by teachers and incompatible with the society of the other children, Lambert finds himself rejected by the world. He finds no more success in Paris, where he is led to "eat my heart out in misery". He becomes a vegetable, removed from the physical world entirely.

As a reflection of Balzac himself, Lambert also embodies the author's self-image as a brilliant writer, but one who acknowledges suspicions about his mental health. Some of his stories and public statements – as well as his fall prior to writing the novel – had led some observers to question Balzac's sanity. The protagonist's madness in ''Louis Lambert'' only added weight to these claims. As biographer Graham Robb writes: "It was typical of Balzac to douse a fire with petrol."

Reception and legacy

Balzac was fiercely proud of ''Louis Lambert'' and believed that it elegantly represented his diverse interests in philosophy, mysticism, religion, and occultism. When he sent an early draft to his lover at the time, however, she predicted the negative reception it would receive. "Let the whole world see you for themselves, my dearest," she wrote, "but do not cry out to them to admire you, because then the most powerful magnifying glasses will be directed at you, and what becomes of the most exquisite object when it is put under a microscope?" Critical reaction was overwhelmingly negative, due mostly to the book's lack of sustaining narrative. Conservative commentator Eugène Poitou, on the other hand, accused Balzac of lacking true faith and portraying the French family as a vile institution.

Balzac was undeterred by the negative reactions; referring to ''Louis Lambert'' and the other works in ''Le Livre mystique'', he wrote: "Those are books that I create for myself and for a few others." Although he was often critical of Balzac's work, French author

Balzac was fiercely proud of ''Louis Lambert'' and believed that it elegantly represented his diverse interests in philosophy, mysticism, religion, and occultism. When he sent an early draft to his lover at the time, however, she predicted the negative reception it would receive. "Let the whole world see you for themselves, my dearest," she wrote, "but do not cry out to them to admire you, because then the most powerful magnifying glasses will be directed at you, and what becomes of the most exquisite object when it is put under a microscope?" Critical reaction was overwhelmingly negative, due mostly to the book's lack of sustaining narrative. Conservative commentator Eugène Poitou, on the other hand, accused Balzac of lacking true faith and portraying the French family as a vile institution.

Balzac was undeterred by the negative reactions; referring to ''Louis Lambert'' and the other works in ''Le Livre mystique'', he wrote: "Those are books that I create for myself and for a few others." Although he was often critical of Balzac's work, French author Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , , ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. Highly influential, he has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flauber ...

was influenced – perhaps unconsciously – by the book. His own story "La Spirale", written in the 1850s, bears a strong plot resemblance to Balzac's 1832 novel.

While the three editions of ''Louis Lambert'' were being revised and published, Balzac was developing a scheme to organize all of his novels – written and unwritten. He called the scheme ''La Comédie humaine

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figure ...

'' ("The Human Comedy"), and envisioned it as a panoramic look at every part of French life at the time. He placed ''Louis Lambert'' in the section named ''Études philosophiques'' ("Philosophical Studies"), where it remained throughout his fifteen-year refinement of the project. He returned to the themes of the novel in his later work ''Séraphîta'', which follows the travails of an androgynous

Androgyny is the possession of both masculine and feminine characteristics. Androgyny may be expressed with regard to biological sex, gender identity, or gender expression.

When ''androgyny'' refers to mixed biological sex characteristics i ...

angelic creature. Balzac also inserted Lambert and his lover Pauline into later works – as he often did with characters from earlier novels – most notably in the story '' Un drame au bord de la mer'' ("A Drama at the Sea's Edge").Hunt, p. 135; Pugh, pp. 52–53.

Notes

Bibliography

* Affron, Charles. ''Patterns of Failure in La Comédie Humaine''. New Haven:Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

, 1966. .

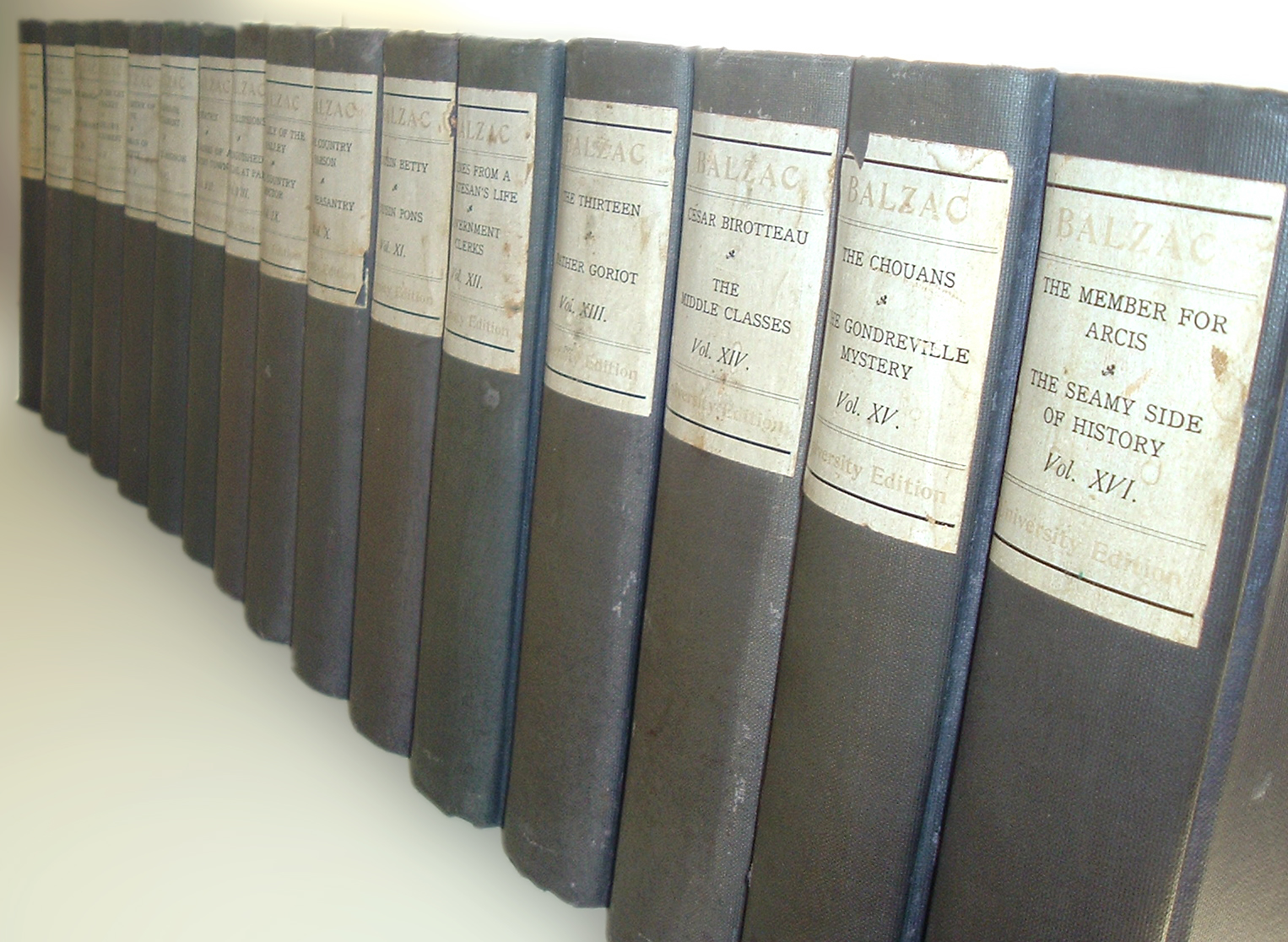

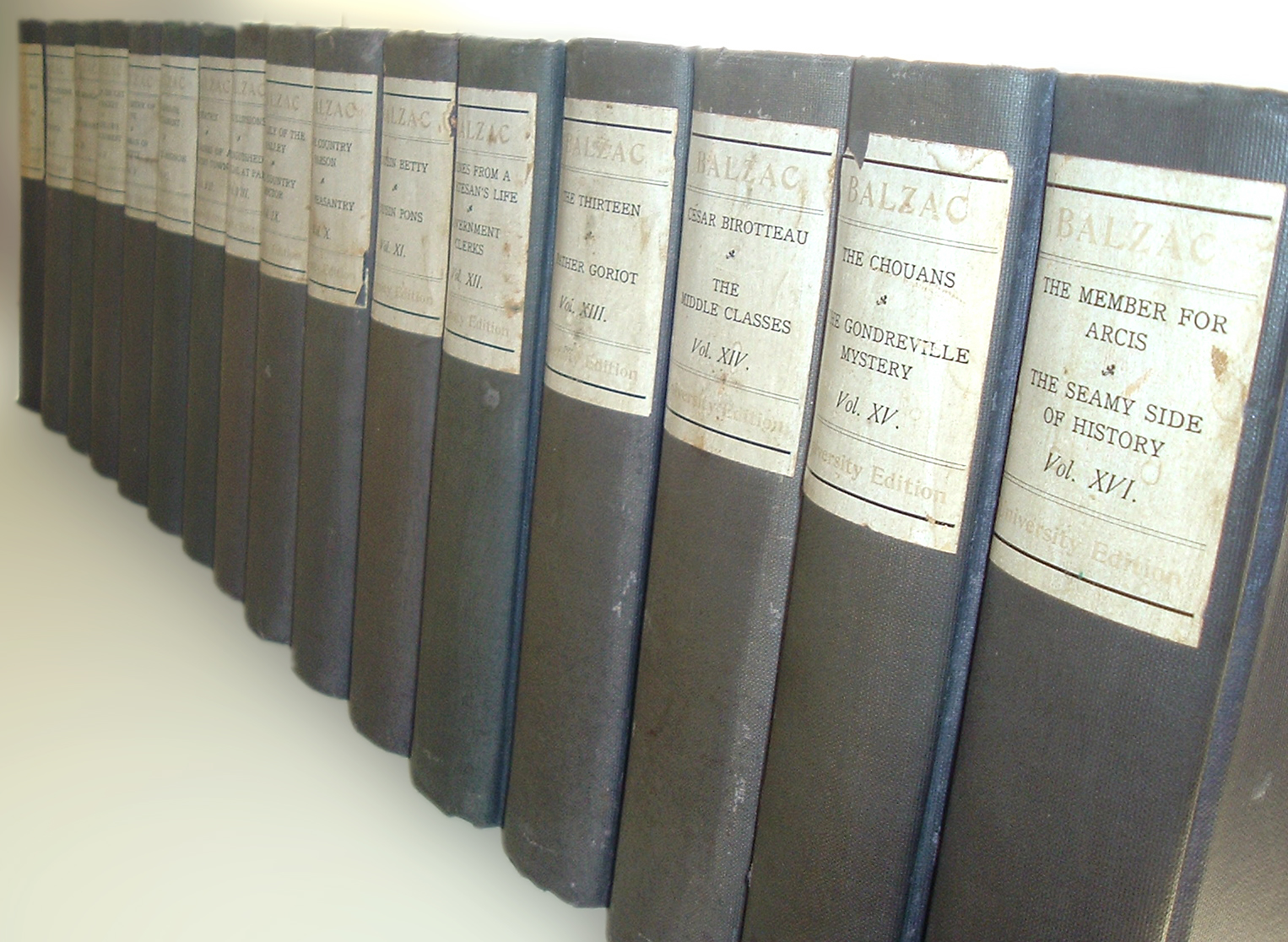

* Balzac, Honoré de. ''Louis Lambert''. ''The Works of Honoré de Balzac''. Vol. II. Philadelphia: Avil Publishing Company, 1901. .

* Bellos, David. ''Balzac Criticism in France, 1850–1900: The Making of a Reputation''. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976. .

* Bertault, Philippe. ''Balzac and the Human Comedy''. Trans. Richard Monges. New York: New York University Press

New York University Press (or NYU Press) is a university press that is part of New York University.

History

NYU Press was founded in 1916 by the then chancellor of NYU, Elmer Ellsworth Brown.

Directors

* Arthur Huntington Nason, 1916–1932 ...

, 1963. .

* Dedinsky, Brucia L. "Development of the Scheme of the ''Comedie Humaine'': Distribution of the Stories". ''The Evolution of Balzac's Comédie humaine''. Ed. E. Preston Dargan and Bernard Weinberg. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

, 1942. . pp. 22–187.

* Hunt, Herbert J. ''Balzac's Comédie Humaine''. London: University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

Athlone Press, 1959. .

* Marceau, Felicien. ''Balzac and His World''. Trans. Derek Coltman. New York: The Orion Press, 1966. .

* Maurois, André. ''Prometheus: The Life of Balzac''. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1965. .

* Oliver, E. J. ''Balzac the European''. London: Sheed and Ward, 1959. .

* Pugh, Anthony R. ''Balzac's Recurring Characters''. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press founded in 1901. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university calen ...

, 1974. .

* Robb, Graham. ''Balzac: A Biography''. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994. .

* Rogers, Samuel. ''Balzac & The Novel''. New York: Octagon Books, 1953. .

* Saintsbury, George. "Introduction". ''The Works of Honoré de Balzac''. Vol. II. Philadelphia: Avil Publishing Company, 1901. . pp. ix–xiii.

* Sprenger, Scott.Balzac as Anthropologist

(on Louis Lambert). ''Anthropoetics'' VI, 1, 2000, 1–15. * Sprenger, Scott. ""Balzac, Archéologue de la conscience," Archéomanie: La mémoire en ruines, eds.Valérie-Angélique Deshoulières et Pascal Vacher, Clermont Ferrand: Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal, CRLMC, 2000, 97–114. * Stowe, William W. ''Balzac, James, and the Realistic Novel''. Princeton:

Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financial su ...

, 1983. .

External links

''Louis Lambert''

at

Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a Virtual volunteering, volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the ...

*

{{Authority control

1832 French novels

Books of La Comédie humaine

French-language novels

Novels set in high schools and secondary schools

Emanuel Swedenborg

Novels by Honoré de Balzac